Free Eye of Horus Tarot Card Reading

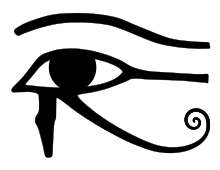

The wedjat center, symbolizing the Eye of Horus

The Eye of Horus, wedjat middle or udjat eye is a concept and symbol in ancient Egyptian religion that represents well-being, healing, and protection. It derives from the mythical disharmonize between the god Horus with his rival Set, in which Gear up tore out or destroyed 1 or both of Horus's eyes and the centre was subsequently healed or returned to Horus with the assist of another deity, such as Thoth. Horus subsequently offered the eye to his deceased male parent Osiris, and its revivifying power sustained Osiris in the afterlife. The Eye of Horus was thus equated with funerary offerings, besides as with all the offerings given to deities in temple ritual. Information technology could also represent other concepts, such as the moon, whose waxing and waning was likened to the injury and restoration of the eye.

The Center of Horus symbol, a stylized middle with distinctive markings, was believed to have protective magical power and appeared frequently in ancient Egyptian fine art. It was i of the most common motifs for amulets, remaining in use from the Sometime Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BC) to the Roman menstruum (30 BC – 641 AD). Pairs of Horus eyes were painted on coffins during the Start Intermediate Menstruum (c. 2181–2055 BC) and Eye Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC). Other contexts where the symbol appeared include on carved stone stelae and on the bows of boats. To some extent the symbol was adopted past the people of regions neighboring Egypt, such as Syria, Canaan, and peculiarly Nubia.

The heart symbol was also rendered as a hieroglyph (𓂀). Egyptologists accept long believed that hieroglyphs representing pieces of the symbol stand for fractions in ancient Egyptian mathematics, although this hypothesis has been challenged.

Origins

Amulet from the tomb of Tutankhamun, fourteenth century BC, incorporating the Eye of Horus beneath a disk and crescent symbol representing the moon[one]

The ancient Egyptian god Horus was a sky deity, and many Egyptian texts say that Horus'south right heart was the sun and his left eye the moon.[2] The solar middle and lunar eye were sometimes equated with the red and white crown of Egypt, respectively.[3] Some texts treat the Center of Horus seemingly interchangeably with the Centre of Ra,[4] which in other contexts is an extension of the power of the sun god Ra and is often personified as a goddess.[v] The Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson believes the two optics of Horus gradually became distinguished as the lunar Eye of Horus and the solar Eye of Ra.[6] Other Egyptologists, nonetheless, contend that no text clearly equates the eyes of Horus with the dominicus and moon until the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BC);[vii] Rolf Krauss argues that the Heart of Horus originally represented Venus every bit the morning time star and evening star and only later became equated with the moon.[8]

Katja Goebs argues that the myths surrounding the Eye of Horus and the Eye of Ra are based around the same mytheme, or cadre element of a myth, and that "rather than postulating a single, original myth of ane cosmic body, which was then merged with others, it might be more fruitful to recollect in terms of a (flexible) myth based on the structural human relationship of an Object that is missing, or located far from its owner". In the myths surrounding the Eye of Ra, the goddess flees Ra and is brought dorsum by another deity. In the case of the Center of Horus, the heart is ordinarily missing because of Horus'due south disharmonize with his arch-rival, the god Ready, in their struggle for the kingship of Egypt after the death of Horus's father Osiris.[ix]

Mythology

Figurine of Thoth, in the form of a birdie, belongings the wedjat eye, seventh to 4th century BC

The Pyramid Texts, which appointment to the late Onetime Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BC), are 1 of the primeval sources for Egyptian myth.[10] They prominently feature the conflict between Horus and Fix,[11] and the Centre of Horus is mentioned in about a quarter of the utterances that make up the Pyramid Texts.[7] In these texts, Gear up is said to have stolen the Eye of Horus, and sometimes to have trampled and eaten information technology. Horus still takes back the eye, ordinarily by strength. The texts often mention the theft of Horus's eye forth with the loss of Set's testicles, an injury that is also healed.[12] The disharmonize over the eye is mentioned and elaborated in many texts from later times. In most of these texts, the eye is restored by another deity, most normally Thoth, who was said to take made peace between Horus and Set up. In some versions, Thoth is said to have reassembled the middle subsequently Fix tore information technology to pieces.[13] In the Book of the Dead from the New Kingdom, Set up is said to have taken the form of a black boar when striking Horus's heart.[xiv] In "The Contendings of Horus and Set", a text from the belatedly New Kingdom that relates the conflict as a brusque narrative, Ready tears out both of Horus's eyes and buries them, and the next morn they grow into lotuses. Here information technology is the goddess Hathor who restores Horus's eyes, by anointing them with the milk of a gazelle.[thirteen] In Papyrus Jumilhac, a mythological text from early on in the Ptolemaic Menstruum (332–30 BC), Horus'southward mother Isis waters the buried pair of eyes, causing them to abound into the first grape vines.[15]

The restoration of the centre was ofttimes referred to as "filling" the eye. Hathor filled Horus'southward centre sockets with the gazelle'south milk,[16] while texts from temples of the Greco-Roman era said that Thoth, together with a grouping of 14 other deities, filled the eye with specific plants and minerals.[17] The procedure of filling the Eye of Horus was likened to the waxing of the moon, and the fifteen deities in the Greco-Roman texts represented the 15 days from the new moon to the full moon.[17]

The Egyptologist Herman te Velde suggests that the Centre of Horus is linked with some other episode in the conflict between the two gods, in which Set subjects Horus to a sexual assault and, in retaliation, Isis and Horus cause Set to ingest Horus's semen. This episode is narrated most clearly in "The Contendings of Horus and Ready", in which Horus'due south semen appears on Ready's forehead equally a gold deejay, which Thoth places on his own head. Other references in Egyptian texts imply that in some versions of the myth it was Thoth himself who came forth from Fix's head after Set was impregnated past Horus's semen, and a passage in the Pyramid Texts says the Eye of Horus came from Set's forehead. Te Velde argues that the disk that emerges from Set's caput is the Eye of Horus. If so, the episodes of mutilation and sexual abuse would form a single story, in which Fix assaults Horus and loses semen to him, Horus retaliates and impregnates Set, and Set up comes into possession of Horus's eye when it appears on Set's caput. Because Thoth is a moon deity in addition to his other functions, it would make sense, according to te Velde, for Thoth to sally in the course of the center and step in to make peace between the feuding deities.[18]

Beginning in the New Kingdom,[17] the Eye of Horus was known equally the wḏꜣt (ofttimes rendered equally wedjat or udjat), meaning the "whole", "completed", or "uninjured" eye.[iii] [nineteen] It is unclear whether the term wḏꜣt refers to the heart that was destroyed and restored, or to the one that Fix left unharmed.[20]

A personified Eye of Horus offers incense to the enthroned god Osiris in a painting from the tomb of Pashedu, thirteenth century BC[one]

Upon condign king after Set's defeat, Horus gives offerings to his deceased father, thus reviving and sustaining him in the afterlife. This act was the mythic prototype for the offerings to the dead that were a major function of aboriginal Egyptian funerary customs. Information technology also influenced the conception of offer rites that were performed on behalf of deities in temples.[21] Among the offerings Horus gives is his own eye, which Osiris consumes. The center, as part of Osiris'southward son, is ultimately derived from Osiris himself. Therefore, the eye in this context represents the Egyptian conception of offerings. The gods were responsible for the existence of all the appurtenances that they were offered, and so offerings were function of the gods' own substance. In receiving offerings, deities were replenished by their own life forcefulness, equally Osiris was when he consumed the Heart of Horus. In the Egyptian worldview, life was a forcefulness that originated with the gods and circulated through the world, so that by returning this force to the gods, offering rites maintained the flow of life.[22] [23] The offering of the centre to Osiris is another example of the mytheme in which a deity in need receives an eye and is restored to well-being.[24] The middle's restorative ability meant the Egyptians considered information technology a symbol of protection against evil, in addition to its other meanings.[20]

In ritual

Offerings and festivals

In the Osiris myth the offering of the Eye of Horus to Osiris was the prototype of all funerary offerings, and indeed of all offer rites, as the human giving an offering to a deity was likened to Horus and the deity receiving it was likened to Osiris.[25] Moreover, the Egyptian give-and-take for "eye", jrt, resembled jrj, the discussion for "human action", and through wordplay the Center of Horus could thus exist equated with whatever ritual act. For these reasons, the Eye of Horus symbolized all the sustenance given to the gods in the temple cult.[26] The versions of the myth in which flowers or grapevines grow from the buried eyes reinforce the eye'south relationship with ritual offerings, as the perfumes, food, and beverage that were derived from these plants were commonly used in offering rites.[27] The heart was frequently equated with maat, the Egyptian concept of cosmic gild, which was dependent on the continuation of the temple cult and could likewise be equated with offerings of whatsoever kind.[23]

The Egyptians observed several festivals in the grade of each calendar month that were based on the phases of the moon, such equally the Blacked-out Moon Festival (the first of the month), the Monthly Festival (the second day), and the Half-Month Festival. During these festivals, living people gave offerings to the deceased. The festivals were frequently mentioned in funerary texts. Beginning in the fourth dimension of the Coffin Texts from the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC), funerary texts parallel the progression of these festivals, and hence the waxing of the moon, with the healing of the Eye of Horus.[28]

Healing texts

Ancient Egyptian medicine involved both practical treatments and rituals that invoked divine powers, and Egyptian medical papyri do not conspicuously distinguish the two. Healing rituals oft equate patients with Horus, then the patient may be healed equally Horus was in myth.[29] For this reason, the Middle of Horus is ofttimes mentioned in such spells. The Hearst papyrus, for case, equates the physician performing the ritual to "Thoth, the dr. of the Middle of Horus" and equates the instrument with which the physician measures the medicine with "the measure with which Horus measured his eye". The Centre of Horus was particularly invoked as protection against eye affliction.[30] One text, Papyrus Leiden I 348, equates each role of a person's body with a deity in order to protect it. The left eye is equated with the Eye of Horus.[31]

Symbol

Horus was represented as a falcon, such as a lanner or peregrine falcon, or as a human being with a falcon head.[32] The Eye of Horus is a stylized human being or falcon eye. The symbol often includes an eyebrow, a nighttime line extending behind the rear corner of the heart, a cheek marking beneath the heart or forwards corner of the center, and a line extending below and toward the rear of the eye that ends in a curl or spiral. The cheek marking resembles that constitute on many falcons. The Egyptologist Richard H. Wilkinson suggests that the curling line is derived from the facial markings of the chetah, which the Egyptians associated with the sky because the spots in its coat were likened to stars.[1]

The stylized eye symbol was used interchangeably to represent the Center of Ra. Egyptologists often simply refer to this symbol as the wedjat middle.[33]

Amulets

A variety of wedjat eye amulets

Amulets in the shape of the wedjat eye first appeared in the late Old Kingdom and connected to be produced up to Roman times.[20] Ancient Egyptians were usually buried with amulets, and the Eye of Horus was i of the most consistently pop forms of amulet. It is one of the few types ordinarily found on Old Kingdom mummies, and it remained in widespread use over the adjacent two one thousand years, fifty-fifty as the number and diverseness of funerary amulets greatly increased. Up until the New Kingdom, funerary wedjat amulets tended to be placed on the chest, whereas during and after the New Kingdom they were commonly placed over the incision through which the body's internal organs had been removed during the mummification process.[34]

Wedjat amulets were made from a wide diverseness of materials, including Egyptian faience, drinking glass, gold, and semiprecious stones such equally lapis lazuli. Their class also varied profoundly. These amulets could stand for correct or left eyes, and the eye could be formed of openwork, incorporated into a plaque, or reduced to little more than than an outline of the eye shape, with minimal ornament to bespeak the position of the pupil and brow. In the New Kingdom, elaborate forms appeared: a uraeus, or rearing cobra, could announced at the front of the eye; the rear screw could become a bird's tail feathers; and the cheek mark could be a bird's leg or a human arm.[35] Cobras and felines often represented the Eye of Ra, so Center of Horus amulets that incorporate uraei or feline body parts may represent the human relationship between the two eyes, as may amulets that acquit the wedjat eye on one side and the figure of a goddess on the other.[36] The 3rd Intermediate Menstruum (c. 1070–664 BC) saw still more complex designs, in which multiple modest figures of animals or deities were inserted in the gaps betwixt the parts of the eye, or in which the eyes were grouped into sets of four.[35]

The middle symbol could too be incorporated into larger pieces of jewelry alongside other protective symbols, such as the ankh and djed signs and various emblems of deities.[37] Start in the thirteenth century BC, drinking glass beads begetting middle-like spots were strung on necklaces together with wedjat amulets, which may be the origin of the modern nazar, a type of bead meant to ward off the evil heart.[38]

Sometimes temporary amulets were created for protective purposes in especially dangerous situations, such as affliction or childbirth. Rubrics for ritual spells frequently instruct the practitioner to draw the wedjat heart on linen or papyrus to serve as a temporary amulet.[39]

Other uses

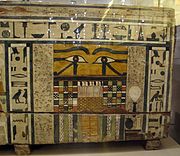

Wedjat eyes appeared in a wide diversity of contexts in Egyptian art. Coffins of the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BC) and Middle Kingdom often included a pair of wedjat eyes painted on the left side. Mummies at this time were often turned to face up left, suggesting that the optics were meant to permit the deceased to see outside the coffin, simply the optics were probably also meant to ward off danger. Similarly, eyes of Horus were oftentimes painted on the bows of boats, which may have been meant to both protect the vessel and allow it to see the way ahead. Wedjat eys were sometimes portrayed with wings, hovering protectively over kings or deities.[six] Stelae, or carved stone slabs, were often inscribed with wedjat eyes. In some periods of Egyptian history, only deities or kings could be portrayed directly beneath the winged sun symbol that frequently appeared in the lunettes of stelae, and Eyes of Horus were placed above figures of common people.[forty] The symbol could besides exist incorporated into tattoos, as demonstrated by the mummy of a woman from the late New Kingdom that was decorated with elaborate tattoos, including several wedjat optics.[41]

Some cultures neighboring Egypt adopted the wedjat symbol for utilise in their own art. Some Egyptian creative motifs became widespread in art from Canaan and Syrian arab republic during the Eye Bronze Age. Art of this era sometimes incorporated the wedjat, though it was much more than rare than other Egyptian symbols such as the ankh.[42] In dissimilarity, the wedjat appeared ofttimes in art of the Kingdom of Kush in Nubia, in the first millennium BC and early beginning millennium AD, demonstrating Egypt's heavy influence upon Kush.[43] Downwardly to the present twenty-four hour period, eyes are painted on the bows of ships in many Mediterranean countries, a custom that may descend from the use of the wedjat eye on boats.[44]

-

Wedjat optics on the coffin of Irinimenpu, twentieth to seventeenth century BC

-

Winged wedjat eyes on the coffin of Henettawy, tenth century BC

-

Wedjat eyes atop the stela of Uhemmenu, sixteenth century BC

-

Crown from the post-Meroitic period in Nubia, c. 350–600 AD, incorporating multiple wedjat eyes

Hieroglyphic form

| |

| wedjat or Eye of Horus |

|---|

| Gardiner: D10 |

| Egyptian hieroglyphs |

A hieroglyphic version of the wedjat symbol, labeled D10 in the list of hieroglyphic signs drawn upwards by the Egyptologist Alan Gardiner, was used in writing as a determinative or ideogram for the Eye of Horus.[45]

The Egyptians sometimes used signs that represented pieces of the wedjat eye hieroglyph. In 1911, the Egyptologist Georg Möller noted that on New Kingdom "votive cubits", inscribed rock objects with a length of one cubit, these hieroglyphs were inscribed together with similarly shaped symbols in the hieratic writing system, a cursive writing system whose signs derived from hieroglyphs. The hieratic signs stood for fractions of a hekat, the basic Egyptian measure out of volume. Möller hypothesized that the Horus-center hieroglyphs were the original hieroglyphic forms of the hieratic fraction signs, and that the inner corner of the centre stood for ane/2, the pupil for 1/4, the countenance for 1/8, the outer corner for i/16, the curling line for i/32, and the cheek mark for 1/64. In 1923, T. Eric Peet pointed out that the hieroglyphs representing pieces of the middle are not establish before the New Kingdom, and he suggested that the hieratic fraction signs had a dissever origin but were reinterpreted during the New Kingdom to take a connection with the Middle of Horus. In the same decade, Möller's hypothesis was included in standard reference works on the Egyptian language, such as Ägyptische Grammatik by Adolf Erman and Egyptian Grammar by Alan Gardiner. Gardiner's treatment of the subject suggested that the parts of the heart were used to correspond fractions because in myth the center was torn apart by Set and later fabricated whole. Egyptologists accepted Gardiner's estimation for decades afterward.[46]

Jim Ritter, a historian of scientific discipline and mathematics, analyzed the shape of the hieratic signs through Egyptian history in 2002. He concluded that "the further back we go the farther the hieratic signs diverge from their supposed Horus-eye counterparts", thus undermining Möller'due south hypothesis. He also reexamined the votive cubits and argued that they practise not conspicuously equate the Centre of Horus signs with the hieratic fractions, so even Peet's weaker form of the hypothesis was unlikely to be correct.[47] All the same, the 2014 edition of James P. Allen's Middle Egyptian, an introductory book on the Egyptian language, still lists the pieces of the wedjat eye as representing fractions of a hekat.[45]

The hieroglyph for the Center of Horus is listed in the Egyptian Hieroglyphs block of the Unicode standard for encoding symbols in computing, as U+13080 (𓂀). The hieroglyphs for parts of the heart (𓂁, 𓂂, 𓂃, 𓂄, 𓂅, 𓂆, 𓂇) are listed as U+13081 through U+13087.[48]

| Preview | 𓂀 | 𓂁 | 𓂂 | 𓂃 | 𓂄 | 𓂅 | 𓂆 | 𓂇 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPH D010 | EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPH D011 | EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPH D012 | EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPH D013 | EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPH D014 | EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPH D015 | EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPH D016 | EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPH D017 | ||||||||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | december | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex | dec | hex |

| Unicode | 77952 | U+13080 | 77953 | U+13081 | 77954 | U+13082 | 77955 | U+13083 | 77956 | U+13084 | 77957 | U+13085 | 77958 | U+13086 | 77959 | U+13087 |

| UTF-8 | 240 147 130 128 | F0 93 82 80 | 240 147 130 129 | F0 93 82 81 | 240 147 130 130 | F0 93 82 82 | 240 147 130 131 | F0 93 82 83 | 240 147 130 132 | F0 93 82 84 | 240 147 130 133 | F0 93 82 85 | 240 147 130 134 | F0 93 82 86 | 240 147 130 135 | F0 93 82 87 |

| UTF-16 | 55308 56448 | D80C DC80 | 55308 56449 | D80C DC81 | 55308 56450 | D80C DC82 | 55308 56451 | D80C DC83 | 55308 56452 | D80C DC84 | 55308 56453 | D80C DC85 | 55308 56454 | D80C DC86 | 55308 56455 | D80C DC87 |

| Numeric character reference | 𓂀 | 𓂀 | 𓂁 | 𓂁 | 𓂂 | 𓂂 | 𓂃 | 𓂃 | 𓂄 | 𓂄 | 𓂅 | 𓂅 | 𓂆 | 𓂆 | 𓂇 | 𓂇 |

Citations

- ^ a b c Wilkinson 1992, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Wilkinson 1992, pp. 43, 83.

- ^ a b Pinch 2002, p. 131.

- ^ Krauss 2002, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Compression 2002, pp. 64, 128.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 1992, p. 43.

- ^ a b Eaton 2011, p. 238.

- ^ Krauss 2002, pp. 193–195.

- ^ Goebs 2002, pp. 45, 57.

- ^ Pinch 2002, pp. 9, 11.

- ^ Griffiths 1960, p. 1.

- ^ Griffiths 1960, pp. two–4.

- ^ a b Pinch 2002, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Griffiths 1960, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Turner 2013, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Eaton 2011, p. 239.

- ^ a b c Kaper 2001, p. 481.

- ^ te Velde 1967, pp. 43–46.

- ^ Faulkner 1991, pp. 74–75.

- ^ a b c Andrews 1994, p. 43.

- ^ Assmann 2001, pp. fifty–51.

- ^ Frandsen 1989, pp. 97–98.

- ^ a b Shafer 1997, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Goebs 2002, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Assmann 2001, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Lorton 1999, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Pinch 2002, p. 132.

- ^ Eaton 2011, pp. 232, 238–239.

- ^ Compression 2006, pp. 133–135, 140.

- ^ Griffiths 1960, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Pinch 2006, p. 142.

- ^ Bailleul-LeSuer 2012, pp. 33, 174.

- ^ Pinch 2006, p. 29.

- ^ Ikram & Dodson 1998, pp. 138–140, 143.

- ^ a b Andrews 1994, p. 44.

- ^ Darnell1997, pp. 36–38.

- ^ Pinch 2006, pp. 111, 116.

- ^ Potts 1982, pp. 20–25.

- ^ Compression 2006, pp. 105, 110.

- ^ Robins 2008, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Watson 2016.

- ^ Teissier 1996, pp. xii, 49.

- ^ Elhassan 2004, p. thirteen.

- ^ Potts 1982, p. xix.

- ^ a b Allen 2014, p. 472.

- ^ Ritter 2002, pp. 297–302, 307.

- ^ Ritter 2002, pp. 306, 309–311.

- ^ Unicode 2020.

Works cited

- Allen, James P. (2014). Center Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Civilisation of Hieroglyphs, Tertiary Edition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-1-107-05364-9.

- Andrews, Ballad (1994). Amulets of Ancient Egypt . University of Texas Press. ISBN978-0-292-70464-0.

- Assmann, Jan (2001) [German language edition 1984]. The Search for God in Ancient Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Cornell University Printing. ISBN978-0-8014-3786-1.

- Bailleul-LeSuer, Rozenn, ed. (2012). Betwixt Heaven and World: Birds in Aboriginal Egypt. The Oriental Plant of the University of Chicago. ISBN978-1-885923-92-9.

- Darnell, John Coleman (1997). "The Apotropaic Goddess in the centre". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 24: 35–48. JSTOR 25152728.

- Eaton, Katherine (2011). "Monthly Lunar Festivals in the Mortuary Realm: Historical Patterns and Symbolic Motifs". Journal of About Eastern Studies. 70 (2): 229–245. doi:10.1086/661260. JSTOR 661260. S2CID 163404019.

- Elhassan, Ahmed Abuelgasim (2004). Religious Motifs in Meroitic Painted and Stamped Pottery. Archaeopress. ISBN978-1-84171-377-9.

- Faulkner, Raymond O. (1991) [1962]. A Curtailed Dictionary of Heart Egyptian. Griffith Institute. ISBN978-0-900416-32-3.

- Frandsen, Paul John (1989). "Trade and Cult". In Englund, Gertie (ed.). The Faith of the Ancient Egyptians: Cognitive Structures and Pop Expressions. Due south. Academiae Ubsaliensis. ISBN978-91-554-2433-6.

- Goebs, Katja (2002). "A Functional Approach to Egyptian Myth and Mythemes". Journal of Ancient About Eastern Religions. 2 (1): 27–59. doi:x.1163/156921202762733879.

- Griffiths, J. Gwyn (1960). The Conflict of Horus and Seth. Liverpool Academy Press.

- Ikram, Salima; Dodson, Aidan (1998). The Mummy in Aboriginal Egypt: Equipping the Dead for Eternity. Thames & Hudson. ISBN978-0-500-05088-0.

- Kaper, Olaf E. (2001). "Myths: Lunar Myths". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 480–482. ISBN978-0-nineteen-510234-five.

- Krauss, Rolf (2002). "The Eye of Horus and the Planet Venus: Astronomical and Mythological References". In Steele, John M.; Imhausen, Annette (eds.). Under One Sky: Astronomy and Mathematics in the Aboriginal Near Eastward. Ugarit-Verlag. pp. 193–208. ISBNiii-934628-26-5.

- Lorton, David (1999). "The Theology of Cult Statues in Ancient Egypt". In Dick, Michael B. (ed.). Born in Heaven, Fabricated on Earth: The Making of the Cult Image in the Ancient Near East. Eisenbrauns. pp. 123–210. ISBN978-i-57506-024-8.

- Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Egyptian Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Goddesses, and Traditions of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-xix-517024-v.

- Pinch, Geraldine (2006). Magic in Ancient Egypt, Revised Edition. University of Texas Press/British Museum Press. ISBN978-0-292-72262-0.

- Potts, Albert M. (1982). The Globe'due south Eye. Academy Press of Kentucky. ISBN978-0-8131-1387-half-dozen.

- Ritter, Jim (2002). "Closing the Eye of Horus: The Ascent and Fall of 'Horus-eye Fractions'". In Steele, John M.; Imhausen, Annette (eds.). Under One Sky: Astronomy and Mathematics in the Ancient Well-nigh East. Ugarit-Verlag. pp. 297–323. ISBNiii-934628-26-5.

- Robins, Gay (2008). The Art of Aboriginal Egypt, Revised Edition. Harvard Academy Press. ISBN978-0-674-03065-7.

- Shafer, Byron Eastward (1997). "Temples, Priests, and Rituals: An Overview". In Shafer, Byron E (ed.). Temples of Ancient Egypt. Cornell University Press. pp. ane–30. ISBN0-8014-3399-1.

- Teissier, Beatrice (1996). Egyptian Iconography on Syro-Palestinian Cylinder Seals of the Heart Bronze Age. Academic Press Fribourg / Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen. ISBN 978-3-7278-1039-8 / ISBN 978-3-525-53892-0

- Turner, Philip John (2013). Seth: A Misrepresented God in the Ancient Egyptian Pantheon?. Archaeopress. ISBN978-1-4073-1084-viii.

- te Velde, Herman (1967). Seth, God of Defoliation. Translated by G. East. Van Baaren-Pape. Eastward.J. Brill.

- "Unicode 13.0 Grapheme Code Charts: Egyptian Hieroglyphs" (PDF). Unicode Consortium. 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Watson, Traci (12 May 2016). "Intricate animal and flower tattoos institute on Egyptian mummy". Nature. 53 (155): 155. Bibcode:2016Natur.533..155W. doi:x.1038/nature.2016.19864. S2CID 4465165. Retrieved xvi May 2021.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (1992). Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Aboriginal Egyptian Painting and Sculpture. Thames & Hudson. ISBN978-0-500-05064-4.

Farther reading

- Rudnitsky, Günter (1956). Dice Aussage über "das Auge des Horus" (in German). Ejnar Munksgaard.

- Westendorf, Wolfhart (1980). "Horusauge". In Helck, Wolfgang; Otto, Eberhard; Westendorf, Wolfhart (eds.). Lexikon der Ägyptologie (in German language). Vol. 3. Harrassowitz. pp. 48–51. ISBN978-three-447-02100-v.

External links

-

Media related to Centre of Horus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Centre of Horus at Wikimedia Commons

schweitzerthess1965.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eye_of_Horus

0 Response to "Free Eye of Horus Tarot Card Reading"

Post a Comment